Negotiating the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework

Tough negotiations at COP15 lead to post-2020 Biodiversity Framework that prioritises economic interests over broader value systems

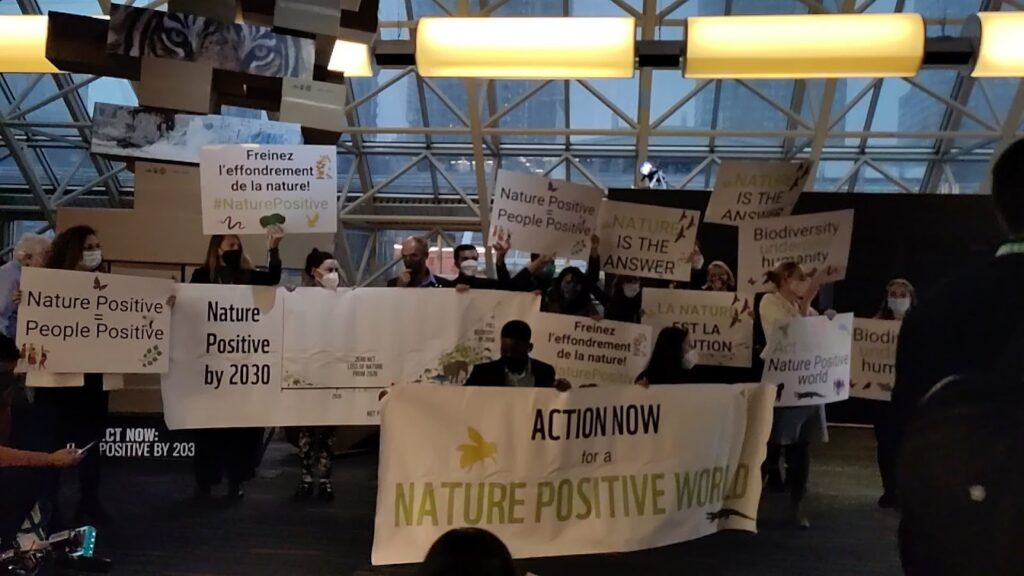

Signatories to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity congregated in Montréal between the 7th and 19th of December at the fifteenth meeting of the Conference of Parties (CoP-15) to agree on the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). Our colleagues Dr Alison Hutchinson and Dr Teresa Lappe-Osthege closely followed negotiations over the first week of the CoP.

The post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework identifies a set of goals and specific targets to halt biodiversity loss, redirect conservation efforts, and shape human-nature interactions over the next decade. Following the complete failure of nations to meet the Aichi biodiversity targets, negotiations for the GBF risked losing momentum as the exact wording of the text was rephrased, re-worked, and watered down considerably during the Convention.

Arriving at the draft agreement

An open-ended working group on the post-2020 framework was tasked with clearing contentious sections of the draft agreement before the official start of the CoP (3rd to 5th December); however, fundamental disagreements over the overarching outlook of the agreement hindered significant progress. More serious commitments and compromises were urgently needed from the national parties, but with a delay of more than two years due to the COVID-19 pandemic, negotiations in Montréal were off to a slow start. The predominantly anthropocentric tone of the draft agreement, emphasising ‘nature-positive’ solutions and economic cost-benefit models, clashed with approaches to biodiversity conservation that are based on the intrinsic values of nature (e.g. forefronting the rights of ‘Mother Earth’). The latter could not be ubiquitously translated into quantifiable targets and despite a focus on nature, anthropocentric and Eurocentric viewpoints dominated within discussions.

The open-ended working group had 23 targets and several sections on the purpose and implementation of the agreement to 2030 (as well as a vision for 2050) to agree upon. With limited time, negotiations failed to find consensus on many points with much of the text remaining within brackets to be debated further within CoP-15. Strong frontiers between negotiating parties became particularly evident during the plenary of the open-ended working group when some countries stalled the session in order to make last-minute changes to previously agreed sections of text, significantly weakening the agreement and endangering entire targets before CoP-15 had officially started (this was the case for what was target 21, now target 22 on gender-responsive participation).

Areas of contention

Subsequent negotiations proved difficult, particularly those linked to a) resource mobilisation (how would these decisions be funded and who should be responsible for paying?), b) digital sequence information and genetic resources (this relates to genetic and biological digital information, with impacts on the breeding of plants and animals, the development of pharmaceuticals, and for synthesising wildlife ingredients – with benefit sharing being a key concern here), and c) requirements for planning, monitoring, reporting, and capacity building, as well as mechanisms for technical and scientific cooperation.

Throughout the convention space it would appear that the 30×30 target (protecting 30% of the planet by 2030) was already agreed upon, but within the working groups and informal meeting rooms the allocation and division of protected terrestrial, inland water, coastal, and marine areas continued to be contested. Rhetorical appeals to collective action amidst immediate crises were plentiful, with Co-Chairs rallying parties to stop ‘fighting a war on nature’ and to ‘make peace with nature’ instead. This rhetoric, however, indicates that we’re once again looking at risks of fortress conservation models being repeated, excluding local communities and indigenous peoples from conservation areas and reinforcing an uneven distribution of both the cost and benefits of biodiversity loss and conservation. These issues were frequently reflected in discussions, particularly around who is responsible for paying for biodiversity restoration, conservation, and management, and how the benefits from biodiversity will be shared amongst parties. Recognising the rights of nature, including Mother Earth as a subject of law, conflicts with current commodification models for conservation which are balanced upon sustainable development and growth objectives. Calls to end ‘the war on nature’ raise significant questions of how the rights of nature will be recognised in international policies and action.

The new post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework

Following these intense and overall sticky negotiations, the new post-2020 GBF aims to tackle questions of the rights of nature by acknowledging indigenous peoples and local communities as the ‘custodians of biodiversity’ (Section C.8) and integrating diverse value systems into its implementation (Section C.9). However, zooming in on the 23 targets of the agreements, particularly those on sustainable use of nature (e.g. targets 5 and 9), the economic valuation of biodiversity for human benefit clearly dominates over the rights of nature. Perhaps most controversially, the 30×30 target, which sees 30 percent of terrestrial and marine areas placed under ‘sustainable management’ (targets 2 and 3) has been agreed upon by the signatory parties. Expanding protection to areas of ‘particular importance for biodiversity’ (e.g., within the Global South) has the potential to reinforce a separation between people and nature. The success of such a target will rely upon conservation governance arrangements including indigenous people and local communities in decision-making (Section C.8) to sidestep a history of colonial conservation logics and re-balance historical and existing power inequalities.

Putting ‘nature on a path to recovery for the benefit of people and planet’ (2050 vision) raises the question of just what is meant by ‘nature’ and whose values are represented within this vision? While the GBF considers diverse values for nature, the interpretation remains in the hands of individual countries who may choose to prioritise business models for conservation (e.g. ecosystem services) while ambitions to live in harmony with nature and Mother Earth remain less well defined. Issues around financing for the biodiversity targets have proved particularly controversial (the delegate from the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s objections to the signing of the GBF on the basis of funding availability was seemingly overruled at the last minute), and concerns were raised by some African, South Asian and South American countries over who would pay for such transformative changes. While these concerns are framed by socio-economic, structural and power divides, they also risk becoming a new form of biodiversity offset payments, allowing richer countries to offset destructive practices via biodiversity and conservation related funding. It remains to be seen if expanding protections for terrestrial, water and seascapes will enable a more holistic approach to conserve and protect nature, or if it will act as a mechanism for businesses, corporations and elites in the Global North to finance new ‘green’ development schemes under the guise of biodiversity management.

While the final agreement appears to have abandoned the rhetoric of ‘nature positivity’, its underlying logic remains, with businesses encouraged but not required to reduce negative impacts on biodiversity, disclose risks, report on compliance, and ensure sustainable patterns of production (target 15). Target 5 focuses on the use, harvesting and trade of wild species and is of particular interest within our Beastly Business project. We are glad to see the focus on wild species (not just those who are recognised as threatened), which is seemingly also inclusive of fisheries and forests. The challenge now lies in how industries built on wildlife exploitation will transition toward sustainable, safe, and legal trade, and what the responses to their counterparts (unsustainable, unsafe, and illegal) will be. Just how the ambitions of the GBF will be measured, monitored, managed and funded is as yet undecided. While, on paper, the targets recognise the severe challenges facing all life on Earth, the agreement is not legally binding and progress will be measured in the good faith and cooperation for transformative change made by all of its members.