by Rosaleen Duffy, George Iordachescu, Dominique C Thompson

The new Successful Wildlife Crime Prosecution in Europe (SWiPE) report is a very detailed analysis of the dimensions of wildlife crime and policy responses in 11 case study countries. The report rightly states that Europe is a key crossroads for wildlife trafficking, but is also a site of wildlife crime threatening European species. It is essential to move away from the over-focus on Africa and Asia as the ‘central problems’ in wildlife crime; such a focus renders wildlife crime in Europe invisible. The Beastly Business project was specifically designed to put a spotlight on illegal wildlife trade in Europe, and so this new SWiPE report is a very welcome development.

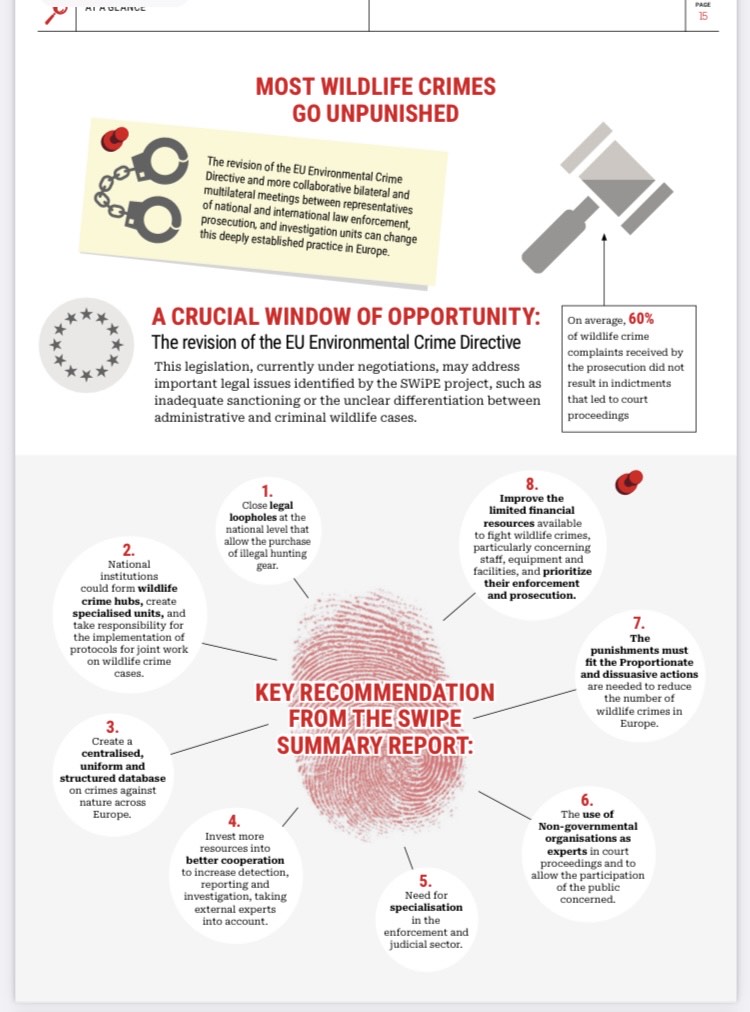

SWiPE was established in 2020 to discourage and reduce wildlife crime by improving compliance with EU environmental law and to contribute to a more successful prosecution of wildlife crimes. The SWiPE project is comprised of 13 partners in 11 European countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Spain, and Ukraine) and is funded by the EU LIFE Programme. During 2022 the team produced 11 national level reports on wildlife crime but this new report is an overview and synthesis of those individual reports.

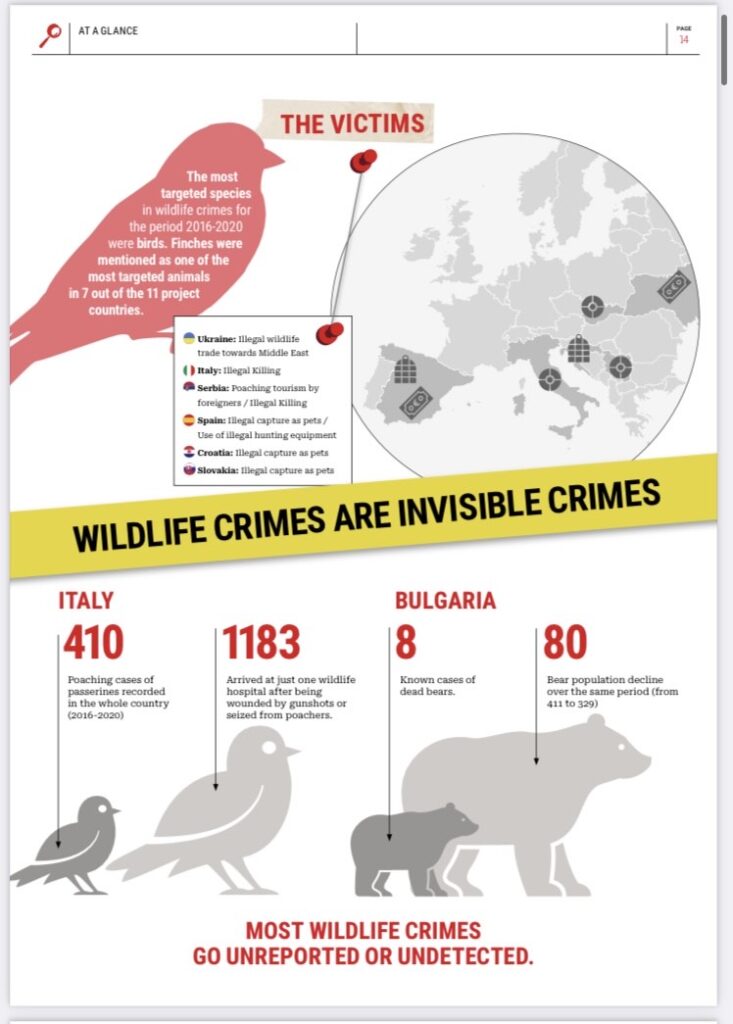

It starts with the bold statement that ‘Despite a regulatory framework consisting of different international conventions and EU legal instruments, wildlife crime (WLC) is an increasing concern in Europe due to a relatively low risk of detection, shortcomings in law enforcement and prosecution, and potential high gains for offenders’. (p7) This very much intersects with the findings of our Beastly Business project, focusing on illegal wildlife trade in brown bears, songbirds and European eel. There are several areas where the report dovetails with our own research on the limitations produced by scientific uncertainty, the importance of legal loopholes, issues with implementation of the law and defining animals affected as victims of crime subject to serious harms.

Scientific Uncertainty

First, the report emphasises the scientific uncertainty surrounding the status of different species, and the accuracy of data on law enforcement. Each country uses different methods and reporting structures which makes it difficult to draw comparisons between case studies (p.15). Indeed the report calls for a common set of databases across the SWiPE project countries to address the need for more accurate and complete data on the patterns of wildlife crime and information on law enforcement. There is a need to have a common approach for collecting data on incidences of wildlife crime, seizures and prosecutions. We show that controversies over scientific knowledge not only impairs uniform and effective enforcement of environmental regulations, but it also hinders the creation of effective management and conservation measures for protecting European species.

Legal loopholes

Second, our own research shows that legal loopholes and disconnections between different legislative arrangements can facilitate wildlife crime. The SWiPE report also indicates that disconnections in legislation provide loopholes that create opportunities for illegal activity. Furthermore, in most case study states there was an unclear distinction of whether wildlife crime should be treated as an administrative offence or a criminal offence (p33); this means that wildlife crimes are often dealt with as administrative offences because they are deemed not to reach a threshold of damage to qualify it as a criminal office – and these tend to carry much lighter penalties. We take this argument further and show how legal disconnects favour the creation of grey markets and illicit activities associated with illegal wildlife trade. For example, illegal trophy hunting of brown bears in Romania could be conducted using legal covers under yearly intervention quotas or exceptional derogations from the Habitats Directive. Similarly, because a legally mandated traceability mechanism for the European eel is lacking, the trafficking of this species could be facilitated within the European common market.

Wildlife as Victims

Third, it is especially good to see that the SWiPE report discusses wildlife as victims of crime, and subject to serious harms as a result. The SWiPE report points out that most wildlife crime goes unreported and undetected. Such crimes take place in uninhabited areas with no witnesses. As the report points out, unlike humans, when wildlife goes missing they cannot report themselves as victims (p.53). Very often in debates about wildlife crime, the effects on the animals themselves is overlooked. Green criminologists such as Tanya Wyatt, Angus Nurse and Ragnhild Sollund have done important work in rethinking approaches to wildlife crime that centre the animals themselves and encourage us to define them as victims. Therefore it is essential that the significant harms against wildlife are made more central. In our own work we are developing our thinking around how to highlight harms against wildlife in for example the hunting, trapping, transport and storage of wildlife while they are traded from source to consumer.

Drivers of Demand

Fourth, it is good to see acknowledgement in the SWiPE report of both history and traditions having an impact on WLC and awareness that Europe is a destination for the trafficking of certain protected species in Europe (p64). We identified in our own research that Europe represents a large consumer market for illegal wildlife products and is a key contributor to biodiversity loss across the continent. Our research explores cultural traditions and socio-economic inequalities in Europe as drivers of demand and we set out why it is so important to consider these particular factors and Europe’s role in IWT when formalising policy and enforcement responses.

Further Research

Finally, there are two areas where our work offers possible avenues for further research should there be a follow up SWiPE report: green collar crime and trafficking of European eel.

It is essential to address the role of green collar crime; that is crimes perpetrated by legal actors either knowingly or unknowingly (Van Uhm, 2016). There is a great deal of focus on the role of organized crime in debates about the illegal wildlife trade, and this is reflected in the SWiPE report. In the Beastly Business project we sought to explore the role of green collar crime in wildlife trafficking, and our work showed a wide range of actors including tourism operators, transport and shipping operators and restaurants amongst others who are tied in in a range of ways with illegal trading.

Trafficking of glass eels is a key part of wildlife crime in Europe. However, in the SWiPE report eels are only mentioned once, in relation to Poland. Our other two case study animals feature much more prominently in the report (brown bears and songbirds). In fact in the report it is clear that wildlife crimes against songbirds constitute a key threat – birds were found to be the most persecuted in the 11 case study countries, and songbirds, especially goldfinches, subject to high levels of hunting and trapping. This is in part a result of the choice of case study countries, which are not major eel habitats or where trading eels is not a key economic activity. If there were to be a follow up SWiPE report, it would be important to cover the trafficking of glass eels in order to provide a fuller picture of the dimensions of wildlife crime in Europe.